New Museum of Contemporary Art, Skin Fruit 전시 4/28/10

페이지 정보

작성자 뽕킴 댓글 0건 조회 6,163회 작성일 10-04-30 20:15

본문

New Museum of Contemporary Art / “ Skin Fruit” Exhibition 4/28/09

New Museum 은 1977년에 비영리 재단으로 Marcia Tucker 가 시작했으며, 처음에는 일본 건축회사가 디자인했고, 2007년에 새롭게 디자인해서 다시 지었다. Skin Fruit 전의 전반적인 평은 안 좋다. Non profit organization 으로 알려진 New Museum 이 이런 전시를 한다는 것 자체가 비난을 받는다. Board of Trustee 중의 한 사람인 그리스인 콜렉터 다키스 조아노 Dakis Joannou 의 1500 점 콜렉션 중에 소위 말하는 요즘 잘 나가는 작가의 작품을 빌려와서 전시를 하였다. 작가들은 77년생, 84년생등 어린 작가들이며, 그들의 작품은 비싸서 뮤지엄이 소장할 수가 없으며, 주로 Gagosian Gallery 나 Saatchi Gallery 가 소유하고 있다. 박물관이 전시를 하기 위해서는 collector 들에게 빌려야만 한다.

맨하탄의 비싼 땅에 있는 New Museum 이 입장료만 가지고는 운영되기가 힘들다. 얼마전에는 Carnegie 회사가 200만불을 donation 하였고, 돈이 많은 사람들이 이사회를 구성하고 있다. 상당한 power 를 지닌 New Museum 은 그리스 작가를 promote 하기도 하고, 잘 나가는 작가의 좋은 작품을 가진 뮤지엄으로 단순한 비영리 집단으로 볼 수가 없다. 비평가들은 결과적으로 New Museum 이 collector 를 광고해 주는 역활을 한다고 말한다. Skin Fruit 전에는 Jeff Koons 의 작품도 나왔는데, 콜렉터가 싼 가격일 때 사 놓았다가 지금은 몇천백만불이 되었고, 물론 팔 용의가 있고, auction 에도 간다.

이제 전세계 박물관 사이에 보이지 않는 전쟁이 시작되었다. 친한 collector 를 collect 하면 우리 박물관이 잘 된다. New Museum 의 이사회 멤버인 다키스 조아노가 모마에게 자신의 소장품을 빌려 주지는 않을 것이다. 위트니, 구겐하임, 모마, 뉴 뮤지엄 간의 전쟁이 선포되었다고 할 수있다.

New Museum 의 Skin Fruit 전시는 불편한 작품이 대부분이다. 무엇을 얘기하는지 알 수 없다. Skin Fruit 전의 작품 전반에 흐르고 있는 주제는 body(사람의 몸), sculpture(조각), abject(혐오) 의 three key words 로 mapping 할 수 있다. 대체적으로 전시가 산만하고, 맥락이 없다. 일단 제목은 skin fruit 으로 선정, 외설적으로 잡아놓고, 다키스의 collection 중에 주제에 맞는 것을 추려왔기에 제한이 많다. 결과적으로 돈자랑이며, 뉴 뮤지엄이라는 비영리 공간이 이런 일까지 해야 하나 라는 극단적인 비판을 받는다.

Skin fruit 은 skin flute 에서 나왔으며 남성 성기를 의미하는 slang 인데 feminine 하고 juicy 하게 표현하여 flute 을 fruit 으로 고쳤다. 제목 그대로 skin fruit 전시회에 오면 외설스럽고 지저분한 작품을 보게된다의 의미를 내포한다.

1. Terence Koh, Chocolate Monument, 2006

9/11 을 상기시키는 초꼴렛 기둥이다. 시간이 지나면서 냄새가 나고 가루가 떨어진다. Sculpture 인지 건축물인지 애매하다. 기존의 정해진 장르의 고정 관념을 부셔뜨린다. 작품은 보는 것이라는 생각에서 벗어나 냄새를 맞게 한다. 테렌스 고는 1977년생으로 나이가 어린 작가이며 gay, lesbian issue 를 다루며 performance 를 많이 한다.

2. Charles Ray, Fall’ 91, 1992

키가 큰 마네킹에 옷을 입혔다. 조각이냐? 마네킹이냐? 챨스레이가 직접 만들었으므로 조각이라고 할 수 있는데, 기존 조각의 상징과 의미를 전혀 찾아볼 수가 없다. 기존의 조각은 사람의 아름다움을 표현하거나, 종교의 성스러운 미를 상징했다. 그렇지만 이 작품은 그 어느쪽에도 속하지 않으며, 가르키는 것 하나도 없다. 불쾌하고 짜증이 날 뿐이다. 21세기가 되도록 그 많은 작가들이 무수하게 실험을 하고 난 지금 contemporary sculpture 의 현 주소는 무엇인가? 이 마네킹처럼 아무 것도 지칭하지 않는다.

3. Robert Cuoghi, Pazuzu, 2008

Roberto Cuoghis "Pazuzu" is "a rare Assyrian statuette of a demon god in the Louvre that has been enlarged to a height of 20 feet, its size now commensurate with the fear its subject once inspired."

파주주는 devil 을 상징하는 pagan 이교도의 신으로 루브르 박물관에 있는 작은 figurine 인데, 목에 걸고 다니는 부적으로 사용했던 것을 크게 확대하여 조각처럼 세웠다. 주종교인 기독교도 카톨릭도 아닌 소수 무속 신앙을 큰 규모로 내세우고 있다.

4. Charles Ray, Revolution Counter Revolution

이 회색의 회전 목마는 띡띡 소리만 내고, 체인의 톱니바퀴는 움직이는데 앞으로도 뒤로도 가지 않는다. 한때 아이들이 신나하면서 탔던 원색의 알룩달룩한 목마는 이제 더 이상 아이들에게 appeal 하지 않고, 퇴색된 leisure 문화로 남아 있을 뿐이다. 인간이 역사 속에서 그렇게 오랫동안 혁신과 혁명을 추구했는데, 20, 21 세기 오늘에 인간이 그만큼 더 행복하고 더 착해졌는가? 이 회전 목마는 앞으로도 뒤로도 아닌 제자리 걸음만 계속한 인간 역사의 여러가지 결을 comment 한다.

5. Janine Antoni, Saddle, 2000

눈에 보이는 것은 소가죽인데, 사람들은 안에 사람의 body 가 있는지 없는지가 더 궁금하다. 아예 소가죽은 무시하고 여자가 업드린 조각상이라고 보는 사람도 있다. 사람들은 눈에 보이는 것 밀어내고 보이지도 않는 사람 몸을 구태여 생각한다. 이 작품을 보고 소가죽이다 라고 말하는 사람은 0.001 % 도 안된다. 제닌 안토니는 Saddle 을 가지고 '이게 뭔지 알아 맞추어 봐' 하면서 관객들과 play 를 하고 있다.

6. Pavel Althamers , Schedule of the Crucifix' (2005)

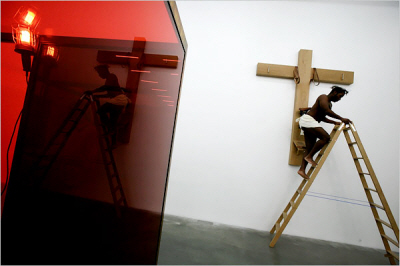

"Pavel Althamer's indisputably iconic 'Schedule of the Crucifix' (2005) consists of a heavy oak cross outfitted with a bicycle seat, straps and handles and accompanied by a folding ladder and screen, also oak.

"The cross will be occupied at unscheduled intervals during museum hours by a man who will change into a loincloth and crown of thorns behind the screen and climb the ladder to his perch."

7. Charles Ray, Aluminum Girl 2003

이게 뭐야? 팔등신도 아니고 머리모양도 촌스럽고 여성누드 stereotype 안에 전혀 안들어 오는 조각이다. 이때까지 여성 누드 조각은 여신이었거나, 옷을 입고 전시 가능한 조각은 성모 마리아 뿐이었다. Aluminum Girl 은 조각도 아니고, 보편적인 여성도 아닌 특정 여자의 몸을 본을 뜬 것이다. 이런 것을 박물관에 놓고 관객보고 뭘 생각 하라는 것인가? 기존의 category 안에 들어오지 않으며 기존 조각의 boundary 를 부셔낸다.

8. Chris Ofili, Rodin the Thinker 1997

나이지리아 태생의 영국 작가인 크리스 오필리는 1999년에 영국의 Saatchi Gallery 가 기획한 Sensation 순회전을 뉴욕 부르크린 뮤지엄에서 열었을때, 흑인 성모 마리아가 코끼리 똥을 뒤집어 쓰고 있는 작품 The Holy Virgin Mary 를 전시했고, 이 작품은 쥴리아니 시장와 뮤지엄이 소송까지 가도록 사회적 issue 를 초래했다. Rodin the Thinker 역시 생각하는 남자를 흑인 여자 창녀로 바꿔놓고 옆에 코끼리 똥을 붙였다. 인간이 혐오 (abject) 스럽다고 느끼는 절대적 지점이 과연 어디인가? 있기는 있는가? 문화마다 해석이 다르다. 코끼리를 섬기는 문명에서는 코끼리의 배설물은 신성하다고 여겨진다. 예술 작품의 고결성의 지점이 어디인가를 질문한다.

9. Tim Noble and Sue Webster, Masters of the Universe 1998-2000

자연사 박물관에나 있음직한 전시가 왜 여기 있을까? 사람의 몸 이야기이다. 500년 후 쯤에는 나를 이렇게 만들어서 옷을 벗기고 ‘2010년에는 인간이 이렇게 생겼었다’ 는 전시를 할지도 모른다. 우리는 지금의 인간 모습이 보편적 진리임을 믿어 의심치 않고, 열심히 인간의 몸에 대한 이야기를 한다. 그렇지만 미래의 관점에서 볼 때 인간의 몸에 대한 현대의 관념들이 meaningless 하다. 왜 인간이 이렇게 고통을 받는가? 질병, 생활고, 스트레스—이 모든 것들, 현재를 절대시 하는 개념에 의한 것이다. 이것을 보고 내가 왜 불편해지는지를 생각하게 하는 전시이다.

10. Maurizio Cattelan, 'Now' 2004

In Maurizio Cattelan's 'Now' . . . a life-size wax effigy of President John F. Kennedy lies in a coffin wearing a dark suit but with bare feet. Into an indelible historical event, it inserts something that never happened: the coffin containing Kennedy’s shattered body was closed when it lay in state.

마치 진짜 장례식에 온 것 처럼 독방에 관이 전시되어 있다. 죽음은 지극히 개인적인 것인데 여기 박물관에 놓임으로서 public 과 private 의 개념이 무너진다. 케네디의 실제의 시체 본체는 흔적도 없으련만, 이 전시에서는 너무나 생생해 시간이 거슬러 간 것 같다. 1963년과 2010년 사이의 47년이라는 시간의 gap 이 너무 커서 놀라는데, 그 사이에 인간의 모습에 gap 이 있는가? Body 의 image 가 너무 직접적이어서 사람들은 skin fruit 전의 전시를 싫어하고 혐오한다. 왜 혐오할까? 내가 회피하는 것을 노골적으로 대놓고 물어보기 때문이다. Abject 의 이면에는 회피가 있으며, 혐오할수록 더욱 멀리 도망간다. ‘예술이 할 일은 이게 아닌데, 일부러 시간내서 돈내고 박물관에 왔는데 왜 불쾌해야 하는지?’ 라고 사람들은 말한다.

11. Maurizio Cattelan, 'All' 2004

시체 안치소 morgue 이다. 제닌 안토닌의 소가죽 안의 사람은 죽은 자인지 살아있는 자인지 가르치지 않는다. 케틀란은 미켈란젤로의 조각에나 썼을 법한 질이 높은 Carrara 대리석으로 All 의 시체를 만들었다. 케틀란의 작품 Now 는 관이 열려 있어서 케네디의 얼굴을 알아본다. 케네디는 살아서도 죽어서도 icon 이다. 케네디 저격수 오스왈드는 옆의 계단에 붙어있고 사람들은 얼굴을 알아본다. 그런데 All 에서는 얼굴도 모르고 누군지도 모른다. 역사 속에는 기억되지 않는 수 많은 사람의 죽음이 계속 반복되는데 오직 ‘1000 명의 죽음’이라는 숫자와 통계로만 남는 반면, 케네디의 죽음은 이렇게 detail 하다. 케틀란은 기억되지 않는 일반 사람들의 죽음을 일부로 비싼 대리석으로 만들어 전시했다.

이 morgue 입구에는 어떤 여자가 벽을 보고 서서 ‘This is a propaganda. You know. You know.’ 라는 노래 퍼포먼스를 하고 있는데, 마치 장례식의 장송곡같이 반복적으로 부르고 있다. 수 많은 사람의 죽음을 정치에 이용하는 프로파간다 (선전) 의 성격이 진하다. ‘수 많은 사람이 희생된 전쟁, 이들의 죽음을 헛되지 않게 하기 위해 나라의 힘을 키워야 한다. 다른 issue 는 다 뒤로 제끼자’

12. Andro Wekua, Sneakers 1, 2008

등에 보이는 다이아몬드 무늬는 피카소의 Harlequin 하르킨에서 광대들이 입었던 옷의 무늬와 같다. 사람들은 광대와 같이 자기 얼굴을 숨기고 가면을 쓰고 산다. 끊임없이 가면을 써서 얼굴은 안 보이는 대신 보라색 스니커가 두드러져 보인다. 타인을 알고 싶어서 남을 판단할 때 몸에 걸친 신, 옷, 가방으로 평가한다. 얼굴을 대신해서 Sneakers 라는 commodity 가 사람의 모습을 보여준다.

Kiki Smith 의 작품 중에 초로 만들어진 여자의 몸이 있는데 전시가 진행되는 동안에 점점 녹아서 흘러 내리고 있었다. 키키의 아버지 Tom Smith 는 미니멀리즘 작가로 모마에 그의 작품이 있으며, modern art 의 역사를 다시 썼다고 평가되는데, 그의 딸 세대는 New Museum 에 자신의 작품을 걸어놓고 ‘ 역사 다 형편없어, 그것 집어치워’ 라고 말하고 있다.

13. Kiki Smith, Mother / Child

같이 보기가 낯이 뜨거운 페미니즘 연장선에 있는 작품이다. 키키는 abject 의 대표작가이며 abject 의 개념을 어머니 몸에서 찾는다. 예술사는 성모 마리아의 마돈나상, 피에타를 통해 어머니와 아이의 관계를 신성 숭고하게 묘사해 왔는데, 키키가 이렇게 역겨운 관계로 만들어 버렸다. 아이가 저런 짓을 하도록 컸는데, 엄마의 젓이 여전히 나오며 그 젓을 아이가 아닌 엄마가 먹고 있다. 아이를 키우면서 (우유를 자신이 먹으면서) 엄마 자신이 큰다. 엄마는 아이를 키우는게 아니라 아이에 대한 obsession 집착을 키운다. 아이의 인생의 dream 에 nurturing 한다. 엄마와 아이의 관계는 혐오스럽고 어머니의 몸은 더욱 혐오스럽다. Charles Ray 는 nostalgia 에는 동전의 양면이 있다고 한다. Nostalgia 가 강하면 강할수록, 그것으로 못 돌아갈까봐, 혹은 못 끊을까봐 horror 가 더욱 크다고 한다.

14. Robert Gober, Two Spread Legs, Highway, Pitched Crib 1987

뒤샹의 ready made --변기, 자전거 바퀴와 비슷한 개념이다. 그런데 irony 는 로버트 거버의 작품은 뒤샹의 개념을 twist 시켜서 hand made ready made 란 점이다. 기존의 뒤샹의 오브제는 뮤지엄을 나가면 다시 상품으로 쓸 수가 있는데 거버의 crib 은 그가 직접 만들어서 다리가 뒤틀리고 엉망이다. 기능 자체를 부셔뜨려서 쓸 수가 없다. 또한 wallpaper 의 벽 사이에 남자의 다리( body part ) 가 삐죽히 나와 있는데, 이 전시의 key word 가 body 임을 상기시키고, 사람의 몸 일부를 가지고 작업한 초현실주의 달리가 연상된다. 달리는 여자 신발, 여자의 몸 일부를 응용했으나, 거버의 작품에는 남자의 다리가 보인다. 역사의 맥락안에서 초현실주의와 dialogue 를 한다.

Paula Jones, 2007. Fiberglass

March 5, 2010

Art Review | 'Skin Fruit'

Anti-Mainstream Museum’s Mainstream Show

By ROBERTA SMITH

The New Museum’s exhibition of artworks from the collection of Dakis Joannou, one of its trustees, has arrived. The project did not sound like a good idea when it was announced last fall. Seeing it up close does not change that.

The show, called “Skin Fruit,” has been selected and chaotically installed (and repulsively titled) by the artist Jeff Koons, an old friend of Mr. Joannou who is also heavily represented in his collection. It fills all the museum’s available gallery space with more than 80 works by 50 artists in multiple mediums: painting, sculpture, drawing, video, performance and installation art.

Sure, “Skin Fruit” includes several outstanding artworks by significant talents, and there are a few genuine surprises. But whether the artists are 1980s stars like Mike Kelley and Cindy Sherman or relative newcomers like John Bock, Nathalie Djurberg and Dan Colen, nearly all are well-known quantities in New York, widely supported by other museums and high on many collectors’ must-have lists. Nearly all emanate from one stratum of the art world: the one where the money is. Is this the most effective way for the New Museum to use its time, space and energy? That’s the question of the art season.

The exhibition drew fire from the get-go — for questionable ethics, for betraying the museum’s original anti-mainstream ethos, for blatantly unmagical curatorial thinking — but the flaws of the real thing turn out to overshadow those early concerns, which can be reasonably disputed. Questions were raised about Mr. Joannou’s relationship with the museum, for example, but trustees frequently show their collections at museums on whose boards they serve, even if they don’t generally take over the whole building. There was worry that the show would increase the value of Mr. Joannou’s holdings, enabling him to make a killing in the art market. But given the size of the art world now, the imprimatur of museums, particularly small ones, is not what it once was, even where the volatile contemporary market is concerned.

One obvious problem, now that the show is in place, is that Mr. Koons, while an extraordinary artist, is an unseasoned curator. An article in the Arts & Leisure section of The New York Times last Sunday indicated that although he himself collects extensively, he leans toward old masters; he seems not to live with the art of his contemporaries, which should have been a big clue. He has also selected more work than the museum’s galleries can comfortably hold, continuing the overcrowded look that is becoming an institutional signature. (To his credit, only one piece is by him: “One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank,” a basketball suspended in water, from 1985.)

In the catalog Mr. Koons describes his selections as “iconic,” which may explain why the works on view tend to be among the best known and most often exhibited in Mr. Joannou’s collection. But a lot of the show feels like filler. Mostly we see above- to below-average examples by usual suspects, most prominently the veteran alpha-artists Richard Prince, Maurizio Cattelan, Urs Fischer, Charles Ray, Chris Ofili, Takashi Murakami and Ms. Sherman. Blue-chipness should not be held against artists, but bringing their efforts together yet again does not an exhibition make. It’s closer to an auction display.

Barely any intellectual glue holds the show together. In her introduction to the catalog, the New Museum’s director, Lisa Phillips, cites the figurative orientation of Mr. Joannou’s holdings, relating it to Classical Greek art and the figurative trend known as “New Images of Man” that followed World War II, mostly in Europe. And certainly a strong affinity for the body and its functions ties together some of the work here — elemental would be a better word than iconic. But this is hardly fresh curatorial territory; such work used to be called abject art. As for viewing abjection through a “New Images of Man” lens, it could be argued that the New Museum did this more effectively and subtly with its “After Nature” exhibition in 2008.

And iconic doesn’t necessarily mean good. In Maurizio Cattelan’s 2004 “Now,” for example, a life-size wax effigy of President John F. Kennedy lies in a coffin wearing a dark suit but with bare feet. Into an indelible historical event, it inserts something that never happened: the coffin containing Kennedy’s shattered body was closed when it lay in state. But despite this twist the piece seems in total little more than an expert, unusually conceptual waxwork.

In contrast Cady Noland’s “Bluewald” (1989) is genuinely iconic. It takes the well-known news photo of Lee Harvey Oswald being shot, presenting only Oswald, much enlarged and printed in red on thick aluminum cut to his form. The shape is penetrated by several large circles — bullet holes — and the one nearest Oswald’s mouth is stuffed with an American flag. The art object, itself cold and cruel, amplifies the violence and shock of the original event as it unfolded before waiting cameras.

For better and worse, this show is strongest in a handful of large pieces that reek of international art festivals and signal Mr. Joannou’s big-game collecting ambitions. Three are jammed together on the fourth floor: “Untitled (Chocolate Mountains),” Terence Koh’s immense twin peaks, implacable landmarks of waste and ruined beauty; Roberto Cuoghi’s towering “Pazuzu,” a rare Assyrian statuette of a demon god in the Louvre that has been enlarged to a height of 20 feet, its size now commensurate with the fear its subject once inspired; and Mr. Ray’s “Revolution Counter-Revolution” (1990/ 2010), a carousel in shades of gray is a characteristic techno-visual tour de force with horses that rotate backward over a base that moves faster to create (sort of) the illusion of forward movement. (No wonder Mr. Ray’s large, girly, full-spectrum ink drawings of flowers in the Whitney Biennial are so refreshing.)

On the third floor Pawel Althamer’s indisputably iconic “Schedule of the Crucifix” (2005) consists of a heavy oak cross outfitted with a bicycle seat, straps and handles and accompanied by a folding ladder and screen, also oak. The cross will be occupied at unscheduled intervals during museum hours by a man who will change into a loincloth and crown of thorns behind the screen and climb the ladder to his perch. Such simplicity belies a complex effect: manned or unmanned, the piece viscerally communicates the performer’s discomfort and by implication, Jesus’ ordeal.

On the second floor David Altmejd’s 2006 sculpture “The Giant,” an enormous male figure festooned with hair, mirror shards and stuffed squirrels — St. Francis as a slightly fatuous bodybuilder — presents an outsize clash of culture and nature that plays on Michelangelo’s David. And the lobby gallery contains John Bock’s stupendous multimedia work “Maltratierte Fregatte” (“Maltreated Frigate”) (2006-7). It centers on a video projection documenting “Medusa in the Tam Tam Club,” a hair-raising, no-noise-barred performance by Mr. Bock and two actors that took place on a school bus suspended vertically above a large backstage area of the Berlin Staatsoper. (Another opera was playing simultaneously in the house, as becomes apparent near the end of the video.) A series of beautifully porous assemblages made during the performance is arrayed in front of the projection, as is the bus, now a crunched mass of bent metal and broken glass. Nestled in its folds is a small monitor on which you can watch two bulldozers in a junkyard downsizing the vehicle — a performance in itself.

It’s interesting to pause and imagine the effect of a show of only these six pieces spread throughout the museum. It would have taken nerve beyond even that of the old, pre-Beacon Dia Center for the Arts, but it might have offered a revelation about art’s need for space that many museums in New York could learn from.

Instead the show is crowded with more normal-size works, a few of which are genuinely wonderful even if they add little of urgency to the exhibition. One is Robert Gober’s 1987 sculpture “Corner Bed,” a fully outfitted single bed looking chaste and awkward against the museum’s white walls. A lushly decorative 1997 painting by Mr. Ofili recasts Rodin’s “Thinker” as a black woman in lacy underthings. Urs Fischer’s grotesque “Noodle” (2009), an enlarged photomontage, builds on the contorted facial expression in Ms. Noland’s “Bluewald.”

Kiki Smith’s “Mother/Child” (1993) consists of life-size beeswax sculptures of a man and a woman pleasuring themselves; it is a study in sexual desperation and shows this uneven, often obvious artist at her toughest. Andro Wekua’s wistful harlequin — another wax figure, from 2008 — is one of his best works. And “Water,” a decidedly un-iconic suite of 51 drawings by Christiana Soulou from the early 1980s is pleasantly unfamiliar; their wispy figures renew the erotic delicacy of artists from Ingres to Hans Bellmer and Jared French.

The low points are many. I’ll mention the sculptures of Paul McCarthy and the team of Tim Noble and Sue Webster for their gratuitous nastiness, and Matt Greene’s student-grade paintings. There is also Mr. Cattelan’s “All” (2007), a largely pointless exercise in high production values: eight life-size, occupied body bags carved in Carrara marble. Intriguingly, this piece was seen in Venice last summer in a dreadful selection from the collection of François Pinault at the insensitively refurbished Punta Della Dogana Museum. What, Mr. Cattelan made enough for all the mega-collectors? How necessary. Seeing the piece here I realized from the varying positions of the figures that they are more likely sleeping than dead, but that didn’t make it any better.

The New Museum reopened in its flashy new building on the Bowery just over two years ago and hit the ground running with an ambitious program of exhibitions that have garnered mixed reviews. “Skin Fruit” should be taken as a chance, if not a wake-up call, for it to ponder seriously its founding principles and its current mission.

I doubt that anyone wants the institution that the visionary curator Marcia Tucker invented and led for 22 years, from 1977 to 1999, to be preserved in amber. Change is inevitable. But just because New York’s larger museums leave a lot to be desired where mainstream contemporary art is concerned, doesn’t mean the New Museum should be rushing in to fill that gap.

The exhibitions during the Tucker years could be infantile, sterile and hectoring, sometimes all at once, but the history they form is a rich resource that the museum neglects at its peril. More than that, the institution’s very size — still small by the standards of art museums — calls for a more tangential, adversarial relationship to the mainstream. Depending on your point of view this exhibition may or may not have an air of complicity, but it definitely has the look of complacency.

“Skin Fruit: Selections From the Dakis Joannou Collection” remains through June 6 at the New Museum, 235 Bowery, at Prince Street, Lower East Side, (212) 219-1222, newmuseum.org.

댓글목록

등록된 댓글이 없습니다.